Throughout America, too many children still lack the support and conditions—health care, economic security, education, adequate nutrition and safety—that they require to grow and flourish. In the 21st century, every child in America should have the freedom to reach their full potential.

As Americans, it is our solemn obligation to help families ensure every child has the support they need, yet we have failed them time and again. In our political system, the best interests of children have often been invoked, but rarely provided for. In recent years, corrupt forces have perverted the basic notion of freedom, while creating a government that works for corporate interests rather than our children’s best interests.

Freedom should not be “reserved for the lucky,” as President Obama once reminded us, but rather is a “commitment[s] we make to each other.”[1] This is especially true for children. The promise of opportunity and freedom for America’s children must be an urgent societal and governmental priority. As former Governor Bob Casey of Pennsylvania wrote,

Only government, when all else fails, can safeguard the vulnerable and powerless. When it [reneges] on that obligation, freedom becomes a hollow word. A hard-working person unable to find work and support his or her family is not free. A person for whom sickness means financial ruin, with no health insurance to soften the blow, is not free. A malnourished child, an uneducated child, a child trapped in foster care—these children are not free. And without a few breaks along the way from government, such children in most cases will never be truly free.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt also understood that living freely required the affirmative work of government and was predicated upon not just the economic well-being of those at the top, but the prosperity and self-determination of all people. In 1941, President. Roosevelt articulated this expansive vision of freedom in his “Four Freedoms” speech,[1] in which he described his vision for a post-war world based on freedom of speech and expression, freedom of every person to worship God in his or her own way, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.[2] Roosevelt’s four freedoms are no less relevant in today’s international order than they were as the world sought to respond to the totalitarian horrors of the 1930s and 1940s.

The last few years have been particularly challenging for American children, but recent political and global events have laid the groundwork for a renewed commitment and ability to revive the true meaning of freedom for all people, and especially for our children, to give them a fair shot to achieve the future they deserve.

Preparing our children for the future, giving them the freedom to develop into the people they aspire to be, requires a deep and continuous commitment on the part of our country and our policymakers. It requires policies and investments that are commensurate with our commitment. To that end, this document sets forth a detailed plan to secure the blessings of freedom for the children of today and tomorrow. This plan identifies five basic freedoms that our society must guarantee to our Nation’s children:

Freedom To Be Healthy

Every child in America should have quality, affordable health care. This proposal recommends automatic Medicaid eligibility at birth through age 18.

Freedom To Be Economically Secure

Every child in America should have the opportunity for economic security, and to earn a living wage when they reach adulthood. This proposal recommends expanding the Child Tax Credit permanently and allowing parents to claim it monthly; and it proposes the creation of children’s saving accounts, seeded annually with $500 in government contributions, that children can later use in pursuit of a post-secondary education, home ownership or a business enterprise.

Freedom To Learn

Every family in America should have access to quality, affordable child care and early learning programs. This proposal recommends an additional annual investment of $7 billion to expand affordable child care and early learning programs, an additional investment of $18 billion annually to ensure that Head Start can cover all eligible 3–5 year old children, and a substantial, permanent expansion of the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit to help working families cover the cost of child care.

Freedom From Hunger

No child in America should go to bed hungry or worried about their next meal. This proposal recommends enhancing automatic certification of more children for school meal programs, expanding universal school lunch and breakfast, and increasing retroactive reimbursement of school meals for eligible children who were not initially certified for school meals.

Freedom To Be Safe From Harm

Every state in the Nation should have the resources necessary to strengthen families, prevent child abuse and neglect, and investigate and prosecute crimes against children. This proposal recommends the following investments: $250 million per year in community-based child abuse prevention; $250 million per year for child protective services; and $250 million per year to state Attorney General offices to prioritize investigation and prosecution of crimes against children.

While the policies outlined here, working in conjunction with one another, would have a substantial and positive impact on the well-being of children, no proposal or document can reasonably cover all of the determinants of child well-being, nor propose policies related to each of them. While this plan focuses on policies that are relatively specific to children themselves, policies related to the well-being and economic security of families are also critically important investments in children. Safe and affordable housing, wage policies such as the minimum wage, as well as paid parental leave, among many others, are directly important for children and for their families.[1]

The election of President Biden has provided an enormous opportunity. President Biden’s American Families Plan seeks to build on the American Rescue Plan (ARP) by proposing a number of transformational and overdue investments in children and their families. With the passage of the American Rescue Plan in March 2021, the United States laid the groundwork for future investments in the well-being of American children and their families. The American Rescue Plan includes historic expansions of three critical, poverty-alleviating tax credits: the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit. These measures will help millions of Pennsylvanians, including 90 percent of Pennsylvania children, during the coronavirus pandemic, invest in our economy and lift half of America’s children out of poverty.

The changes to the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit were based on legislation Senator Casey authored, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit Enhancement Act. This expanded Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit will decrease child poverty, increase employment and earnings, especially for African Americans, single parents, low-income families and mothers younger than 25. The improvements to the Child Tax Credit will support millions of working parents, invest in our economy and cut child poverty in half. Included in the legislation as well were significant investments in child care and early education, as well as important policies intended to prevent hunger and food insecurity, consistent with the original policy recommendations of this document.

Overall, the American Rescue Plan represented a critical and long overdue down payment on meeting our obligations to our children, but it is not enough. Anticipated follow-on legislation proposed by the Biden Administration, the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan, provides an opportunity to extend, solidify and make permanent the work of the American Rescue Plan. We must not squander this opportunity to make the necessary investment in American children.

Recent years have been some of the worst for children in decades, first due to actions taken by the Trump Administration that harmed children substantially and then due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite low unemployment and overall economic growth from 2018–2020, children were too often left out and left behind, a trend only exacerbated by the pandemic. According to the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure, which takes into account many of the government programs designed to assist low-income families and individuals, childhood poverty worsened in 2017 for the first time since the Great Recession.[1] By age group, children are the poorest in the country, accounting for over 31 percent of people in poverty.[2] One out of every five children is poor and one in three children is poor for at least parts of their childhood.[3] Our youngest—infants and toddlers—are the most vulnerable and at-risk for poverty or near poverty.[4], [5]

Poverty harms children both immediately and for a lifetime. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) concluded in their 2019 seminal Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty that poverty itself, especially when it occurs in early childhood or is persistent over time, is damaging to children in ways that last a lifetime.[6] NASEM further estimated that the results of this poverty, in terms of lost adult productivity, increased health costs and increased expenses of crime, cost the United States between $800 billion and $1.1 trillion annually.

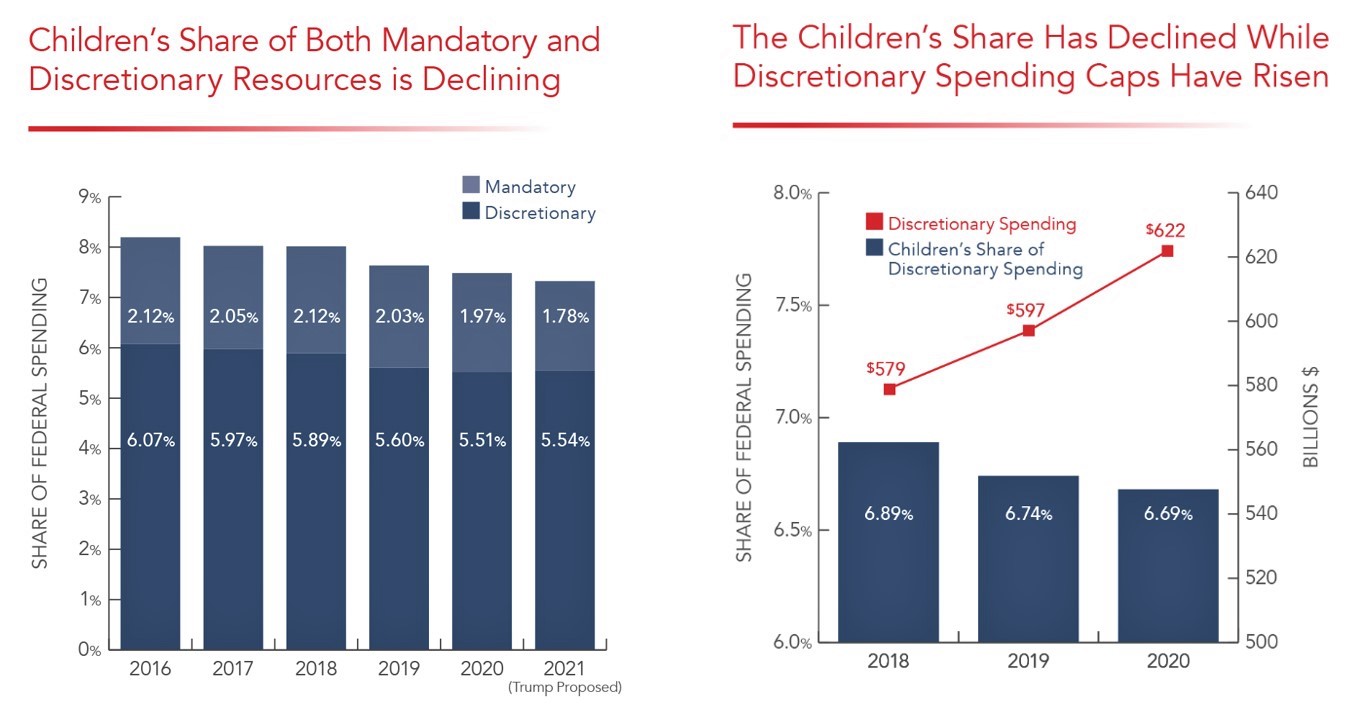

Children’s programs have been woefully underfunded for years, leaving children further and further behind even when federal spending increases in other areas, such as recent legislation to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.[7] Several studies demonstrated the declining share of the federal budget dedicated to child well-being, which in 2020 (not including spending tied to the pandemic response) was estimated to be between 7.48 percent[8] and 9.2 percent. Under pre-pandemic law, that share is expected to fall another two percentage points by 2030. [9]

Measured differently, as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), the same study found similar patterns, with federal spending on children as a percentage of GDP peaking at 2.5 percent of GDP in 2010, declining to 1.9 percent in 2018 and 2019, and then projected to further decline to 1.7 percent by 2030.[1] This decline is worsened by our Nation’s historically low support for children and families when compared with other industrialized countries. As noted in a study published in the journal Academic Pediatrics, “The takeaway is that the United States underinvests in its children and their families and in so doing this leads to high child poverty and poor health and educational outcomes.”[2] Despite increased overall spending, under pre-pandemic law, the federal investment in children is expected to grow by only two cents per dollar increase in expenditures over the next decade.[3]

In fact, the United States ranks nearly dead last compared to other developed nations in terms of percent of GDP invested in early childhood education and care. In 2015, countries such as Iceland, France and Bulgaria spent one percent or more of GDP, while the United States spent less than a half percent.[4] In a world where countries compete for talent and jobs, our country’s lack of investment in our future returns poorer outcomes than so many of our allies and competitors.

Younger children are more likely to live in poverty and to suffer lifelong effects as a result. Therefore, actions to reduce poverty early in life are both crucially important and sadly lacking in the United States. Quality early care and education, which have been shown to both lift children out of poverty and improve educational and life outcomes,[1] are not affordable for most American families. For families with two or more preschool-age children, child care is the biggest annual household expense across most of the country—more than rent or mortgage payments.[2] Child care costs more than college at a public university in 28 states,[3] and is unaffordable for 7 out of 10 American families.[4] Due to years of underinvestment, just one in six children eligible for federal child care assistance receives it.

Children’s safety, especially early in life, is not being adequately addressed. An estimated one in seven children experienced child abuse or neglect in the last year,[5] and children with disabilities are at increased risk.[6] Eighteen hundred and forty children died from abuse or neglect in 2019, with infants being by far the most at risk. Ninety percent of abuse or neglect is committed by parents or caretakers, especially when untreated substance use disorder is present.[7] The opioid crisis and related abuse of other drugs and alcohol have resulted in thousands of children either entering the foster care system or being cared for by other family members.[8] The number of infants entering the foster care system grew by nearly 10,000 each year between 2011 and 2017.[9] Many of these harms have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is a strong consensus in the country that quality education is essential to a child’s ability to learn and be successful. However, education by itself, in the absence of financial security and opportunity, cannot eliminate disparities. Nick Hanauer, founder of the public policy incubator Civic Ventures, recently wrote,

[L]ike many rich Americans, I used to think educational investment could heal the country’s ills—but I was wrong….We should do everything we can to improve our public schools. But our education system cannot compensate for the ways our economic system is failing Americans….American workers are struggling in large part because they are underpaid—and they are underpaid because 40 years of trickle-down policies have rigged the economy in favor of wealthy people like me.

The previous Administration proposed changes to the definition of poverty[1] that would have negatively affected children’s eligibility for health insurance, child care assistance, nutrition assistance and other federal programs. Over time, hundreds of thousands of children could have lost access to food and health care. [2] This is exactly the opposite of the approach we should be taking, as it is precisely these programs that help lift millions of children and families out of poverty and allow them to look forward to the future with hope.

Actions such as the previous Administration’s proposed changes to the “public charge” rules undercut children’s health and well-being in particularly cruel ways.[3] Even before the rule went into effect many parents unenrolled or declined to legally enroll their children in nutrition, health and other programs for fear that doing so would be used against them someday when applying for legal permanent residency or entry into the United States. In 2019, nearly one-third of low-income immigrant families with children, including U.S. citizen children, avoided using public benefits because of green card concerns.[4] Though the Biden Administration reversed this position in March 2021, the chilling effect on immigrant communities may continue into the future, resulting in more illness, more hunger and less success for our children.[5]

Over the past two decades, wealthy Americans and profitable corporations have disproportionately benefited from tax cuts and fiscal policy. Half of American households earn less than $63,000 a year,[6] yet since 2000, we have spent over $1.2 trillion on tax cuts to the top 1 percent.[7] In 1960, the effective tax rate for America’s 400 richest families was 56 percent; in 1980, it was 47 percent; by 2018, it was just 23 percent.[8] The 2017 Republican tax bill[9] is just the most egregious recent example of how spending priorities are completely upside-down, prioritizing corporate giveaways and tax cuts for the wealthy while ignoring priorities like investing in children and building the middle class. Driving growth of debt and deficit through tax cuts for the wealthy and large corporations makes it impossible to invest in our schools, to address child poverty and food insecurity, to tackle maternal mortality, to invest in our roads and bridges, to provide affordable and quality child care and to ensure Americans truly see the benefits from their labor.[10]

There are ample reasons to conclude that the lives of American children are becoming harder every day. The trends of the previous few years—poverty, insurance coverage, food insecurity—have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet with President Biden’s Administration and Democratic control of Congress, we have a new opportunity to halt and even reverse these trends. With the passage of the American Rescue Plan, we have made significant down payments on policies that, if made permanent, would dramatically change the outlook for millions of children in America. This is not the time to rest on our laurels—it is time to put our foot on the gas and make even more progress towards our goal of ensuring every child can grow up healthy, with access to nutritious food and high-quality child care, safe and economically secure.

If we merge mercy with might and might with right then love becomes our legacy and change our children’s birthright.

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children

In the spring and summer of 2020, children were thought to have escaped the worst of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic. Fortunately, children are less susceptible to COVID’s severe and acute physical assaults that resulted in so many adult hospitalizations and death.[1] We have learned, however, that children are by no means immune to the virus. Children have required critical care for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-C), adolescents for respiratory distress, and some have experienced long haul symptoms, even after mild or asymptomatic infection. As so few children were tested for the virus in the early months, we still do not know how many became infected.[2]

The worst of the pandemic for children, however, was the chronic and pervasive disruption of their education, social connectivity, mental health and access to supports, including those normally provided by child care, schools, healthy family members and community services.

Even before we learned of the novel coronavirus, families struggled to find high-quality, affordable child care. As communities shut down to stem transmission of the virus, most child care centers closed and remained shuttered through the summer, straining low-income families and the families of essential workers.[3], [4] Women, in particular, lost income because of child care needs. As the economic fallout of the pandemic continues, nearly three out of four low-income families are struggling to find child care and many can’t return to work until they do.[5]

The pandemic upended learning, school-aged social activities essential to development and the supports our schools provided, including needed meals, school-based healthcare and, for some students, respite from toxic home environments. Remote learning was far from optimal for children who benefit from in-person instruction, particularly those with communication and learning challenges. While the full effect on academic achievement is still unknown, some losses have already been detected; math achievement for students entering grades 3–8 this fall was 5–10 percentage points lower than the year prior.[6] Student absenteeism doubled during the pandemic.[7] The digital divide, separating those with and without adequate devices, reliable Internet, a quiet place to concentrate, and the physical or developmental ability to utilize these tools meant that many children were unable to access education from home. Over 40 percent of children did their homework on a cell phone and nearly the same number depend on public wireless Internet connections.[8]

In addition to academics, our schools provide meals, therapies to children with chronic diseases and mental health services. These critical services sharply declined during the pandemic, with grave consequences. Children went without asthma and diabetes treatments, physical and occupational therapies, and adolescent emergency room visits due to mental health concerns (e.g. anxiety, depression, suicide) increased 24–31 percent.[9],[10]

Prior to the pandemic, routine child health care may have filled the gap. Instead, over the first months of the pandemic, Medicaid and CHIP pediatric visits fell more than 40 percent for preventive health screenings, 44 percent for outpatient mental health services and 75 percent for dental care, delaying diagnoses and treatments.[11] Routine laboratory tests, such as lead screenings, fell by 50 percent compared with the year prior.[12] Childhood vaccination rates plummeted and have not yet recovered.[13]

Even with community supports for education, food, physical and mental health care, children depend on their families to thrive. Raising healthy, thriving, resilient children is more likely in families with parents who feel supported.[14] Conversely, when the adults of those families are strained by job loss, inability to make the rent, hunger, illness and caring for sick relatives, the hardship extends to their children. Chronic, even toxic, stress can have long-term effects on growth, development, learning and functioning.[15] From May to September of 2020, 2.5 million more children fell into poverty.[16] During the pandemic, nearly one in five households with children were behind on rent.[17] Enduring this type of stress during childhood—particularly when it is prolonged—adversely affects brain development, socio-emotional growth, mental health and academic achievement.[18]

[1] Nisha S Mehta, Oliver T Mytton, Edward W S Mullins, Tom A Fowler, Catherine L Falconer, Orla B Murphy, Claudia Langenberg, Wikum J P Jayatunga, Danielle H Eddy, Jonathan S Nguyen-Van-Tam, "SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): What Do We Know About Children? A Systematic Review,” Clinical Infectious Diseases71, no.9, 1 (November 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa556.

[2] “Children & COVID-19: State Level Data Report,” last accessed May 13, 2021, American Academy of Pediatrics, https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/.

[3] “New Survey: Growing Pandemic Challenges for Parents as Fall Approaches,” last accessed May 10, 2021, Bipartisan Policy Center, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/press-release/new-survey-growing-pandemic-challenges-for-parents-as-fall-approaches/.

[4] “The Coronavirus Will Make Child Care Deserts Worse and Exacerbate Inequality,” last accessed May 10, 2021, Urban Institute and Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2020/06/22/486433/coronavirus-will-make-child-care-deserts-worse-exacerbate-inequality.

[5] Holding On Until Help Comes, (NAEYC, Jul 2020) https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf.

[6] Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek and Karen Lewis, “How is Covid-19 Affecting Student Learning,” last accessed May 10, 2021, Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2020/12/03/how-is-covid-19-affecting-student-learning/.

[7] Mark Lieberman, “Five things you need to know about students absences during COVID-19,” last accessed May 10, 2021,Education Week, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/5-things-you-need-to-know-about-student-absences-during-covid-19/2020/10.

[8] Emily A. Volges, Andrew Perrin, Lee Rainie and Monica Anderson, “53% of Americans Say the Internet is Essential During Covid-19 Pandemic,” last accessed May 10, 2021, Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/04/30/53-of-americans-say-the-internet-has-been-essential-during-the-covid-19-outbreak/.

[9] Phyllis Jordan, “Kids lose access to critical health care source when schools shutter due to Covid-10,” last accessed May 10, 2021, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2020/04/06/kids-lose-access-to-critical-health-care-source-when-schools-shutter-due-to-covid-19.

[10] Rebecca T. Leeb, Rebecca H. Bitsko, Lakshmi Radhakrishnan, Pedro Martinez, Rashid Njai, Kristin M. Holland, Mental Health–Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children Aged <18 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, January 1–October 17, 2020, (CDC, Nov 2020), http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3external icon.

[11] Stefanie Polacheck and Hannah Gears, COVID-19 and the Decline of Well-Child Care: Implications for Children, Families, and States, (Center for Health Care Strategies, Oct 2020), https://www.chcs.org/news/covid-19-and-the-decline-of-well-child-care-implications-for-children-families-and-states/.

[12] Brie Zeltner, “Kids Lead Testing Plummets Due to Missed Doctor Visits During Pandemic,” Sep 2020, CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/10/health/lead-poisoning-in-children-wellness-partner/index.html. (Accessed March 21, 2021)

[13] Jean M. Santoli JM et al, Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration—United States, 2020, (CDC, May 2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2.

[14] Mark A.Schuster and Elena Fuentes-Afflick, “Caring for Children by Supporting Parents,” NEJM (Feb 2017), https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1611499.

[15] A Hardship Chain Reaction, (U. Oregon Center for Translational Science, Jul 2020), https://medium.com/rapid-ec-project/a-hardship-chain-reaction-3c3f3577b30.

[16] Zachary Parolin, et al., Monthly Poverty Rates in the Unites States During COVID-19 Pandemic, (Columbia Center for Poverty and Social Policy, 2020), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/5f87c59e4cd0011fabd38973/1602733471158/COVID-Projecting-Poverty-Monthly-CPSP-2020.pdf.

[17] “Household Pulse Surveys, Phase 2,” (US Census Bureau, 2020), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html.

[1] Justin Sink, “Democrats Warn Trump Against Proposed Change to Poverty Measure,” June 13, 2019, Bloomberg Politics, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-13/democrats-warn-trump-against-proposed-change-to-poverty-measure.

[2] Aviva Aron-Dine et al., Administration’s Poverty Line Proposal Would Cut Health, Food Assistance for Millions Over Time (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2019), https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/administrations-poverty-line-proposal-would-cut-health-food.

[3] Robert Greenstein, Trump Administration’s Proposed Rule Will Result in Legal Immigrants of Modest Means Forgoing Needed Benefits, September 9, 2018, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/press/statements/greenstein-trump-administrations-proposed-rule-will-result-in-legal-immigrants-of.

[4] Jennifer M. Haley et al., One in Five Adults in Immigrant Families with Children Reported Chilling Effects on Public Benefit Receipt in 2019 (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2020), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/one-five-adults-immigrant-families-children-reported-chilling-effects-public-benefit-receipt-2019.

[5] Arturo Vargas Bustamante et al., Can Changing the Public Charge Rule Improve the Health and Lives of Children? (The Commonwealth Fund, 2021), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2021/can-changing-public-charge-rule-improve-health-and-lives-children.

[6] Gloria G. Guzman, Household Income: 2017 (United States Census Bureau, 2018), https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/acsbr17-01.pdf.

[7] Steve Wamhoff and Matthew Gardner, Federal Tax Cuts in the Bush, Obama, and Trump Years (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2018), https://itep.org/wp-content/uploads/0710-Federal-Tax-Cuts-in-the-Bush-Obama-and-Trump-Years.pdf.

[8] Aimee Picchi, "America's richest 400 families now pay a lower tax rate than the middle class," October 17, 2019, CBS News, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/americas-richest-400-families-pay-a-lower-tax-rate-than-the-middle-class/.

[9] An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018, P.L. 115–97.

[10] Republican Plans to Cut Taxes Now, Cut Programs Later Would Leave Most Children Worse Off (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 2017), https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/10-18-17bud-onesheet-children.pdf.

[1] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.17226/25246.

[2] The US and the High Cost of Child Care (Child Care Aware of America, 2018) 35-36, https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3957809/COCreport2018_1.pdf.

[3] Claire Zillman, “Childcare Costs More Than College Tuition in 28 U.S. States,” October 22, 2018, FORTUNE, https://fortune.com/2018/10/22/childcare-costs-per-year-us/.

[4] Editorial Staff, “This is how much child care costs in 2019,” July 15, 2019, Care.com, https://www.care.com/c/stories/2423/how-much-does-child-care-cost/.

[5] Preventing Child Abuse & Neglect Factsheet (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/can/CAN-factsheet_508.pdf.

[6] Miriam J. Maclean, et al., “Maltreatment Risk Among Children With Disabilities,” Pediatrics 139, no. 4 (April 2017), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1817.

[7] Child Maltreatment 2017 (United States Department of Health and Human Services Children’s Bureau, 2019), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2017.

[8] Emily Birnbaum and Maya Lora, “Opioid crisis sending thousands of children into foster care,” June 20, 2018, The Hill, https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/393129-opioid-crisis-sending-thousands-of-children-into-foster-care.

[9] Holly Fletcher, “Parental substance use linked to increase in infants in foster care,” July 15, 2019, VUMC Reporter, http://news.vumc.org/2019/07/15/parental-substance-use-linked-to-increase-in-infants-in-foster-care/.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Timothy Smeeding and Céline Thévenot, "Addressing Child Poverty: How Does the United States Compare With Other Nations?", Academic Pediatrics 16, no. 3 (April 2016), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.011.

[3] Heather Hahn et al., Kid’s Share 2020: Report on Federal Expenditures on Children Through 2019 and Future Projections (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2020), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/kids-share-2020-report-federal-expenditures-children-through-2019-and-future-projections/view/full_report.

[4] Public spending on childcare and early education (OECD Social Policy Division Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, March 2019), https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_1_Public_spending_on_childcare_and_early_education.pdf.

[1] Liana Fox, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2017 (Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau, 2018), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-265.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Council on Community Pediatrics, “Poverty and Child Health in the United States,” Itasca, IL: Pediatrics 137, no. 4 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0339.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “High baby and toddler poverty rate a wake-up call for America, leading early childhood development expert says,” September 12, 2018, Zero to Three, https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/2427-high-baby-and-toddler-poverty-rate-a-wake-up-call-for-america-leading-early-childhood-development-expert-says.

[6] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.17226/25246.

[7] Drew Aherne, Michelle Dallafior, Christopher Towner, eds., Children’s Budget 2020 (Washington, DC: First Focus, 2020), https://firstfocus.org/resources/report/childrensbudget2020.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Heather Hahn et al., Kid’s Share 2020: Report on Federal Expenditures on Children Through 2019 and Future Projections (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2020), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/kids-share-2020-report-federal-expenditures-children-through-2019-and-future-projections/view/full_report.

The future which we hold in trust for our own children will be shaped by our fairness to other people's children.

All children deserve a fair start. Regardless of race, ethnicity, family income, physical or developmental attributes, America’s children merit equitable access to health care, education, nutrition and the opportunity to thrive. Yet, for far too long, we have allowed significant disparities to persist, based on the color of one’s skin, zip code or other demographic factors. America can and must do better.

Disparities during childhood lead to outcome gaps in later years, predicting academic achievement, life expectancy and earned income. Children experience discrimination and reduced opportunities not because of their own individual promise or effort, but because they are Black, Hispanic or Native American, because they live in poverty, with a disability or because they express a difference others fear or don’t comprehend. Years of disparate access to diagnoses and treatments, greater burdens of housing and food insecurity, higher rates of victimization, lead to intergenerational health, mental health and educational gaps.[1],[2],[3]

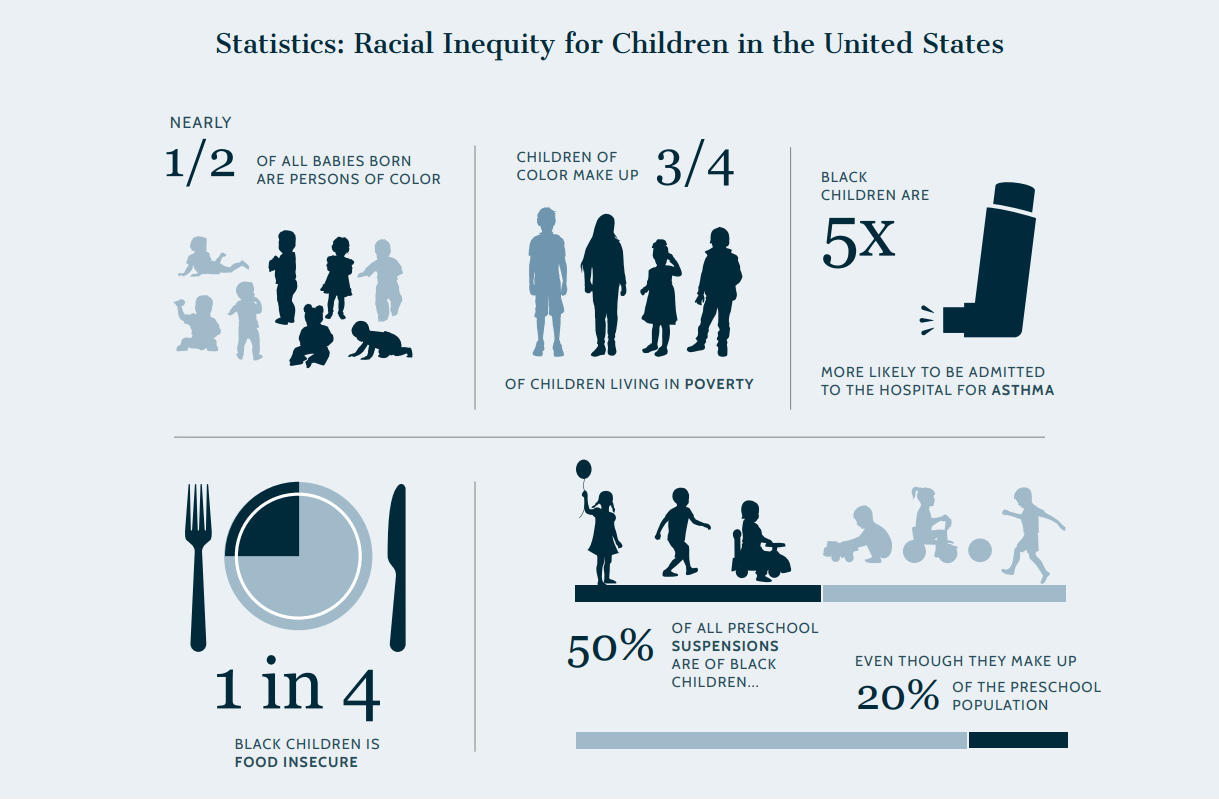

Since 2014, the majority of our public school students are children of color.[4] Nearly half of all babies born in the United States are non-white.[5] Comprising just under half of all children in the United States, children of color account for nearly three-quarters of those living in poverty. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of these children will receive unequal access to education, basic services, provisions and opportunities all children need. Without a level playing field, such children are more likely to suffer from unmet medical needs, nutritional issues, prematurity, infant mortality, trauma and other serious illnesses, including asthma, sepsis and long-term COVID-19 consequences.[6],[7],[8] Black children are nearly five times more likely to be admitted to the hospital for asthma and eight times more likely to die from an asthma attack than white non-Hispanic children.[9]One in four Black children do not know from where their next meal will come, a rate twice as high as that for white children. [10]

Racism is a pervasive public health crisis, associated with increased infant mortality, undiagnosed health conditions, treatment gaps, lack of a medical home and chronic stress.[11], [12] Black and Hispanic children are more likely to grow up in poverty, leading to slower gains in their development, including language, memory and self-regulatory skills.[13] Even those who “make the grade” early on are structurally limited as they grow. Among high performing math students in fifth grade, 60 percent of white students will be enrolled in algebra by eighth grade, compared to just 35 percent of high performing Black students. Just three in 10 high potential black students will enroll in math and science Advanced Placement courses, impacting college admissions and credit waivers.[14]

The first years of life set the path for later success in all realms, including socio-emotional well-being, health, education, employment and later parenting. Research tells us that quality early childhood education is both cost effective and an effective intervention. Yet, we fall short on providing it to our most vulnerable children. Assessing 26 states for both quality and access for Black and Hispanic children, no state provided both.[15] Every day, 250 young children are suspended from preschool; though Black children make up just 19 percent of all enrolled preschoolers, nearly half of the suspensions are given to them.[16]

[1] Nicolaus W. Glomb and Jacqueline Grupp-Phelan, “A Call to Action to Address Disparities in Pediatric Mental Health Care,” Pediatrics 146, no. 4 (Oct 2020), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-018911.

[2] The State of America’s Children 2020 (Children’s Defense Fund, February 2021), https://www.childrensdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-State-Of-Americas-Children-2020.pdf?eid=ytipqVk5TW76b%2FWuOWcNd1SuoYIISO7BQj6P0XeMxmFm%2BJJm0O64en5KnBw90JIO9JugwguvLKraRopD7NG5d4cEYUaGGJu9GCLZ%2FJGqhGNcPV0s.

[3] Jack P. Shonkoff, Natalie Slopen and David R. Williams, “Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health,” Annual Review of Public Health 42 (Apr 2021), https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940.

[4] “Table 203.50. Enrollment and percentage distribution of enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by race/ethnicity and region: Selected years, fall 1995 through fall 2023 in Digest of Education Statistics,” (National Center for Education Statistics, February 2021), https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_203.50.asp.

[5] “Number of Births by Race, 2018” last accessed May 10, 2021, Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/births-by-raceethnicity/?dataView=1¤tTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[6] Monika K Goyal, Joelle N Simpson, Meleah D Boyle, Gia M Badolato, Meghan Delaney, Robert McCarter and Denice Cora-Bramble, “Racial and/or Ethnic Socioeconomic Disparities of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Children,” Pediatrics 146, no.4 (Oct 2020), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-009951.

[7] Anireddy R. Reddy, Monika Goyal, James Chamberlain and Gia Badolato, “Socioeconomic Disparities Associated with Sepsis Mortality,” Pediatrics 144, 2 Meeting Abstract, 404 (Aug 2019), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.144.2_MeetingAbstract.404.

[8] Infant Mortality and African Americans (Office of Minority Health, March 15, 2021) https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23.

[9] “Asthma and African Americans,” (Office of Minority Health, March 15, 2021) https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=15.

[10] The State of America’s Children 2020 (Children’s Defense Fund, February 7, 2021), https://www.childrensdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-State-Of-Americas-Children-2020.pdf?eid=ytipqVk5TW76b%2FWuOWcNd1SuoYIISO7BQj6P0XeMxmFm%2BJJm0O64en5KnBw90JIO9JugwguvLKraRopD7NG5d4cEYUaGGJu9GCLZ%2FJGqhGNcPV0s.

[11] “Transition Plan for Strong Communities: Health Equity and Racism,” American Academy of Pediatrics AAP Blueprints, March 1, 2021, https://services.aap.org/en/advocacy/transition-plan-2020/strong-communities/health-equity-and-racism/.

[12] Eli Rapoport and Andrew Adesman, “State-level Racial Disparities in Medical Home Status in Children in the United States,” Pediatrics 146, 1 Meeting Abstract (Jul 2020); https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.146.1_MeetingAbstract.570.

[13] The State of America’s Children 2020 (Children’s Defense Fund, March 2021), https://www.childrensdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-State-Of-Americas-Children-2020.pdf.

[14] “Opportunity Gaps Drive Achievement Gaps for African American Students,” last accessed May 10, 2021, The Education Trust, https://edtrust.org/the-equity-line/opportunity-gaps-drive-achievement-gaps-for-african-american-students/.

[15] Young Learners/Missed Opportunities: Ensuring That Black and Latino Children Have Access to High-Quality State-Funded Preschool (The Education Trust, Nov 2019), https://edtrustmain.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/05162154/Young-Learners-Missed-Opportunities.pdf.

[16] Delivering on Affirming Early Childhood Education, (NBCDI, May 2019), https://www.nbcdi.org/sites/default/files/import_files/delivering-affirming-early-childhood-education-white-paper.pdf.

Children growing up in rural America are more likely to grow up in poverty and rely on federal supports, and thus are more likely to benefit from increased investments and interventions to improve their well-being. According to the USDA,[1] in 2017, more than one in four rural children under the age of six lived in poverty. Rural children as a whole (age 0–18) were 29 percent more likely than urban children to live in poverty. Forty-three counties in the United States had child poverty rates of 50 percent or higher, 40 of which were rural (93 percent). Eighty-five percent of counties experiencing persistent poverty—defined as 20 percent or more of the population living in poverty for at least 30 years—were rural. Elevated rates of poverty in rural regions are seen in all major racial and ethnic group categories.

Families living in rural areas more commonly face reduced access to employment opportunities, limited public transportation, and inadequate educational, health care and child care options.[2], [3] Rural children are less likely to have health insurance,[4] and infant mortality is substantially higher.[5] Utilization of programs such as WIC[6] and SNAP[7] are higher in rural parts of the country. In 2019, USDA noted that “concentrated poverty contributes to poor housing and health conditions, higher crime and school dropout rates, and employment dislocations,” and that the more time a child spends in poverty or living in a high-poverty area, the more likely they are to be poor as an adult.[8]

Federal health insurance programs play an especially important role in supporting rural children. Families and children residing in rural areas are more likely to be covered by Medicaid than those residing in metropolitan areas. This is not surprising given that rural areas are characterized by lower rates of workforce participation, lower incomes and higher rates of disability.[9] In 2014–2015, 45 percent of children living in rural areas and small towns received health insurance through Medicaid or CHIP, while a significantly smaller percentage, 38 percent, of children living in metropolitan areas did so. This pattern holds true in nearly all states.[10] Similarly, in states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the ACA, small towns and rural areas saw significant benefits. The most dramatic decreases in the uninsured rate were in rural areas of expansion states, where the rate fell from 35 percent to 16 percent, compared to a drop from 38 percent to 32 percent in rural areas of non-expansion states.[11]

[1] “Rural Poverty and Well-Being,” last accessed August 20, 2019, United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/.

[2] “Child Welfare Information Gateway, Rural child welfare practice” (United States Department of Health and Human Services Children’s Bureau, 2018), https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/issue-briefs/rural/.

[3] “Overviews of Specific Issues in a Rural Context,” Rural Health Information Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/rural-toolkit/1/rural-issues.

[4] “Uninsured, Ages 18 and Under, 2017,” April 2019, Rural Health Information Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/charts/3.

[5] “Infant Mortality per 1,000 for Metro and Nonmetro Counties, 2007-2017,” Rural Health Information Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/charts/36.

[6] Rural Hunger in America: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (Washington, DC: Food Research & Action Center (FRAC), July 2018), https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/wic-in-rural-communities.pdf.

[7] Ellen Vollinger, “Rural Areas See Highest SNAP Participation,” NACo County News, June 25, 2018, https://www.naco.org/articles/rural-areas-see-highest-snap-participation.

[8] “Rural Poverty and Well-Being,” last accessed August 20, 2019, United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/.

[9] Julia Foutz, Samantha Artiga and Rachel Garfield, The Role of Medicaid in Rural America (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, April 25, 2017), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue- brief/the-role-of-medicaid-in-rural-america/.

[10] Karina Wagnerman et al., Medicaid in Small Towns and Rural America: A Lifeline for Children, Families, and Communities (Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, June 2017), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Rural-health-final.pdf.

[11] Jack Hoadley et al,. Health Insurance Coverage in Small Towns and Rural America: The Role of Medicaid Expansion (Georgetown University Center For Children and Families, September 25, 2018), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2018/09/25/health-insurance-coverage-in-small-towns-and-rural-america-the-role-of-medicaid-expansion/#easy-footnote-3-34836.

The crisis of freedom facing our Nation’s children is not new or an accident. Over decades, far-right politicians have sought to redefine our Nation’s basic obligations to our children in pursuit of a corporate agenda. This corporate agenda has robbed resources from our schools and health care systems in order to give obscene tax cuts to the super-rich and biggest corporations, as noted above—nearly $1.2 trillion to the top 1 percent in less than 20 years. While pitting Americans against one another, far-right politicians continue to push an agenda that enriches those at the very top. This “trickle down” economic model has funneled wealth upwards, diminished the lives of millions of children, and hoarded opportunity among those who already possess a surplus of it. All of our Nation’s children deserve freedom and the opportunity that comes with being truly free. In the 21st century, the guarantee of freedom must be more than a goal; it must be a matter of national policy.

Our country’s neglect of our children is not a new phenomenon. For decades, we have underinvested in our children. More recently, we witnessed an aggressive acceleration of policies subjecting greater numbers of children to harm. It is time that we make a concerted effort to reverse those trends. Instead of trying to gut Medicaid, disqualify children from food assistance, cage children at the border who are seeking a new life for themselves, or redefine poverty to reduce the number of individuals eligible for means-tested programs, as the previous Administration sought to do, we must instead honor the idea of freedom upon which our Nation was founded and seek to guarantee children’s freedom. A children’s strategy that reflects the value of our Nation’s youngest citizens must do more than move away from harm and beyond neglect. To ensure that America’s future is healthy, robust, inclusive and economically vibrant, we need a proactive model which allocates resources to where they are most needed and which puts in place the conditions under which all children can be truly free.